Leeds law school grad Mohammad Anas takes a deep-dive into the ramifications of Ghibli-style images on copyright law in the era of generative AI

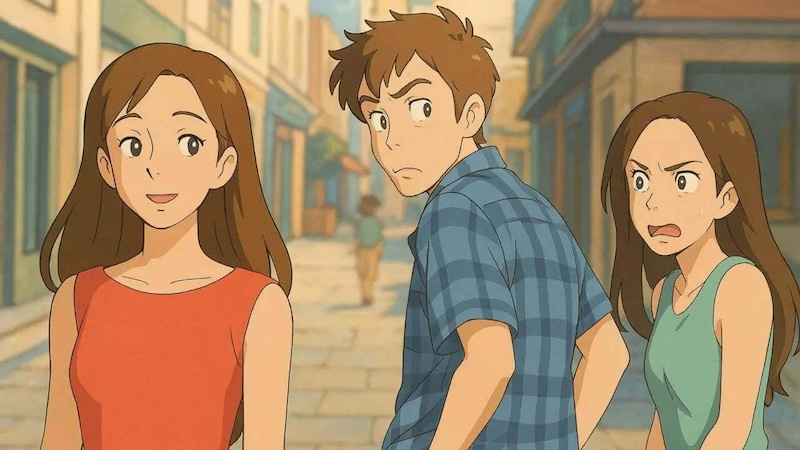

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) presents a formidable challenge to the legal and ethical underpinnings of artistic expression, threatening the integrity of human creativity. This journal examines the 2024 proliferation of Studio Ghibli-style images on X (formerly Twitter) as a pivotal case study, analysing how AI-generated works strain the copyright frameworks of the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the United States.

Through a review of statutory provisions, judicial precedents, and ethical considerations, it exposes systemic deficiencies in current law and the erosion of artistic identity, exemplified by Ghibli’s anti-war, pro-earth, pro-humanity, and anti-consumerist principles.

The threat to creative authorship

In a Tokyo studio, Hayao Miyazaki meticulously crafts Princess Mononoke (1997), each frame a testament to decades of artistic mastery and a philosophy rooted in pacifism, ecological reverence, human dignity, and resistance to consumerism. By 2024, this vision will be replicated on X through AI-generated images of lush landscapes and ethereal figures that echo Ghibli’s aesthetic yet lack its purposeful soul. Concurrently, cartoonist Sarah Andersen confronts the unauthorized appropriation of her distinctive comic style by Stable Diffusion, her creative identity reduced to uncredited algorithmic outputs.

This phenomenon transcends technological innovation, raising profound legal and ethical questions. As copyright systems in the UK, EU, and US grapple with AI’s non-human authorship, they reveal a critical misalignment between statutory intent and modern reality. Can these frameworks adapt to protect the human essence of art epitomised by Ghibli’s principled vision against the systematic challenge posed by generative AI?

Legal frameworks under examination

UK copyright law: A framework under pressure

The Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA) establishes protections for “original artistic works” (s.1(1)(a)), granting authors exclusive rights to control reproduction, adaptation, and distribution (ss.16–20). Infringement hinges on appropriating a “substantial part”, a qualitative standard clarified in Designers Guild Ltd v Russell Williams [2000] 1 WLR 2416. The House of Lords held that this includes both literal copying and the “look and feel” of a work, potentially applicable to AI-generated Ghibli-style images.

However, AI developers invoke the idea-expression dichotomy, upheld in Baigent v Random House [2007] EWCA Civ 247, arguing that style or thematic inspiration falls outside copyright protection. This defence is contested by Temple Island Collections Ltd v New English Teas [2012] EWPCC 1, which protects aesthetic arrangements. Ghibli’s deliberate fusion of anti-consumerist narratives and visual coherence arguably meets this threshold, suggesting a basis for protection against AI mimicry.

Section 9(3) of the CDPA further complicates the issue, attributing authorship of computer-generated works to the person arranging for their creation. In the context of AI, where training datasets are vast and often scraped without consent, this attribution becomes untenable. The case of Getty Images v Stability AI [2023] EWHC challenges the legality of mass scraping under s.17(2), highlighting the lack of clarity on data provenance, leaving artists vulnerable.

Despite these challenges, UK law continues to confront the issue head-on, with some legal scholars proposing that AI-generated works be viewed through a lens of fair use or transformative rights, which could offer a more balanced approach. Others argue that additional protections should be established to address the evolving nature of artistic authorship in the AI age.

EU copyright law: A doctrine misaligned

The EU’s copyright regime, anchored in Directive 2001/29/EC (InfoSoc Directive), requires protection based on the “author’s intellectual creation” (Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening, C-5/08). Ghibli’s works exemplify this, with Miyazaki’s pro-humanity ethos and ecological advocacy. AI-generated facsimiles, however, lack a human author, exploiting a doctrinal gap that undermines this foundation.

The Court of Justice’s ruling in Painer v Standard Verlags GmbH (C-145/10) protects stylistic choices reflecting an author’s personality, yet AI outputs derived from aggregated data challenge this precedent. The EU AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689) mandates data usage disclosure, but its enforcement mechanisms remain superficial, offering limited protection for artists. The current regulatory framework struggles to maintain the balance between allowing AI-driven innovation and preserving the authenticity of artistic authorship.

In practical terms, the lack of data transparency by AI companies poses a significant challenge to the effective enforcement of existing regulations. While some suggest that the AI Act could be a step forward, its applicability to art and creative industries remains unclear and may require further revisions to adequately address AI’s potential to mimic existing styles without permission.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreUS copyright law: A system unprepared

US copyright law demands human authorship, a principle established in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884). The Copyright Office’s 2023 decision on Zarya of the Dawn codifies this, denying protection to AI-generated works. However, this stance leaves rights holders without recourse, particularly concerning the appropriation of existing styles like Ghibli’s anti-war landscapes.

AI developers exploit the Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service (1991) low originality threshold, claiming their outputs transform rather than copy, despite relying on copyrighted inputs. In Andersen v Stability AI (2023), secondary liability is explored, but proving infringement remains difficult due to AI firms’ non-disclosure of data . California’s AB 2013 (2024) mandates AI art transparency, yet federal law remains silent.

Despite these obstacles, recent cases, including Nichols v Universal Pictures (1930), have begun to explore how AI-generated works might be treated under US copyright law, though the absence of clear guidelines leaves both artists and developers in a state of uncertainty. As the technology continues to advance, legal experts are calling for a more robust framework that can handle the complexities of AI-driven creativity.

Ethical dimensions: The value of human intent

Studio Ghibli’s creative process reflects a labour of intent. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) required 14 months of hand-drawn animation, each frame embodying a commitment to peace, ecology, and anti-consumerism . Miyazaki’s rejection of AI art as “an insult to life” resonates with Jung’s view of art as a psychological expression of the human soul, an act irreducible to algorithms. Sarah Andersen’s distress, “my identity, digested by a machine,” highlights the violation of creative agency when her style is mechanized without consent.

The intentionality behind human art is a critical element that AI-generated works cannot replicate. While AI can generate content that mimics existing styles, it lacks the deeper emotional and philosophical contexts that underpin human creation. This absence of agency raises ethical questions about authenticity, responsibility, and the commodification of art in an AI-driven landscape.

Judicial precedents: Seeking clarity

In the UK, Temple Island (2012) protects aesthetic coherence, while Designers Guild (2000) clarifies the “substantial part” standard. In the EU, Painer (2011) safeguards stylistic individuality, while Football Dataco (2012) defends curated effort. In the US, Nichols (1930) fails against AI’s complexity, though Getty v Stability AI (2023) signals a judicial shift toward accountability.

A call for reform: Strengthening legal protections

The UK’s CDPA revisions are stalled, the EU’s AI Act lacks enforceable specificity, and US federal law lags. Current frameworks, built for human authorship, fail to address AI’s appropriation of thematic essence, exposing a critical regulatory gap. Several reforms could help bridge this gap, ensuring artists are better protected while allowing for the responsible use of AI in creative industries.

Proposed Reforms

-

- Mandatory data transparency: Require AI developers to submit training dataset inventories to public registries, verified biannually. Non-compliance should incur fines.

- Strict liability standards: Impose liability for unlicensed use of copyrighted styles, with statutory damages tied to commercial exploitation.

- Redefining ‘substantial part’: Expand the term to include thematic consistency and philosophical intent.

- Artist empowerment mechanisms: Create opt-in registries for creators to license or prohibit AI use of their works.

These reforms shift the burden to AI developers, ensuring artists retain control over their creative legacies.

Conclusion: Upholding the human core of art

The proliferation of AI-generated Ghibli-style images exposes the inadequacies of copyright law in confronting non-human authorship. Yet, the resilience of human creativity persists in its intentionality, vividly embodied in Ghibli’s rejection of war, reverence for nature, celebration of humanity, and critique of consumerism. These principles forged through deliberate labour distinguish art from mechanical imitation. Legal systems must transcend reactive measures and adopt robust transparency and accountability, ensuring creativity remains a human endeavour.

Mohammad Anas is an aspiring solicitor who recently completed his LLB from the University of Leeds, with a strong interest in corporate law, banking and finance, and intellectual property.

The Legal Cheek Journal is sponsored by LPC Law.

(

( (

(