Oxford law grad and aspiring barrister Jordan Briggs wades into the Dominic Cummings saga in this final instalment of a three-part mini-series

Welcome to the third and final article in a mini-series assessing the extent to which the United Kingdom government’s legal response to the coronavirus pandemic complies with the rule of law.

The first article introduced Joseph Raz’s eight-point conception of the rule of law, outlined key coronavirus-related legislation, and described coronavirus laws’ opacity. The second found that coronavirus laws, while themselves ephemeral, are guided by open, stable and clear general rules. It also found that, while the judiciary remain independent and capacious to review implementation of other principles, principles of natural justice seem to have been violated in coronavirus-related prosecutions in Westminster Magistrates’ Court.

This article considers the final two criteria in Raz’s eight-point conception of the rule of law. First, we consider whether courts have been easily accessible during the pandemic. Second, we discuss whether the discretion of crime preventing agencies has been allowed to pervert the law.

Criterion 7. ‘Courts should be easily accessible’

This criterion may have been violated during the pandemic. We will focus here on criminal courts, as their accessibility poses the greatest problem for rule of law purposes. Even before the pandemic, a decade of austerity had caused large backlogs of criminal cases, meaning that one would have to wait for several months (or years) before one’s case could be heard. The problem has only worsened.

Today, the number of cases awaiting trial in the magistrates’ court is the highest it has ever been (517,782 cases) — a growth of 31% since early March. In the same period, the backlog in criminal courts (46,467) has grown 16%. While some of this increase was attributable to the more-or-less inevitable closure of courts in March, practising barristers have attributed the scale of the problem to a sluggish and insufficiently ambitious governmental approach to re-opening court centres.

Joanna Hardy, for example, observed that “Primark had plexiglass screens long before jury boxes did… [and t]he Nightingale courts that arrived with great fanfare were needed months earlier and in greater numbers”. Bernard Richmond suggested that English theatres, cinemas and arts venues could have been used as Nightingale courts, staffed by recorders, so as to deal with “all the short cases which are clogging up the system”.

If we have a month lockdown but jury trials at continuing, how about we put some money into the theatres and cinemas and arts venues & use lots of recorders desperate to work by setting up nightingale courts and doing all the short cases which are clogging up the system

— Bernard Richmond (@phatsilk_qc) October 31, 2020

To their credit the government, evidencing an intention to increase court effectiveness, in July pledged £80 million “for criminal courts to recover from [the] pandemic”, promised to recruit 1,600 new staff and to establish eight more Nightingale Courts. However, it’s unclear whether these measures will be sufficient to effectively remedy the inaccessibility issue. Raynor J of Woolwich Crown Court, in a judgment handed down on 8 September 2020, commented that “£80 million does not, given the scale of the problem, amount to highly significant expenditure” and asserted that, in responding to the pandemic, “the state has failed in its duty to organise its legal systems”.

In sum, the existing practical difficulties associated with accessing criminal courts suggest non-compliance with the rule of law. The government’s willingness to make amends, while commendable, does not itself remedy the issue.

Criterion 8. ‘The discretion of crime preventing agencies may not pervert the law’

There may have been violation of this rule of law criterion. By ‘perversion’, Raz explains that “the prosecution should not be allowed, for example, to decide not to prosecute for commission of certain crimes, or for crimes committed by certain classes of offenders”. Are there instances of the police failing to investigate arguable criminal offences during the coronavirus pandemic? There are.

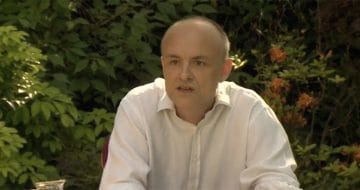

Dominic Cummings is a political strategist who served as chief adviser to Prime Minister Boris Johnson until 13 November 2020. Between March and April 2020, there were (at least) three occasions in which Cummings arguably broke criminal law. The police’s failure to prosecute, if these are arguable cases of illegality, could be interpreted as a breach of the instant criterion of the rule of law.

Want to write for the Legal Cheek Journal?

Find out moreFirst, on the evening of 27 March, Cummings left 10 Downing Street with his family and drove to his parents’ house in Durham. At this time, the law in force was S.I. 2020/350, which criminally proscribed people leaving their place of residence without ‘reasonable excuse’. Did Cummings have a ‘reasonable excuse’? His explanation, given on 25 May, related to childcare. Cummings feared that he and his wife would imminently be weakened by coronavirus, and so drove to his parents’ house to avoid his four-year-old son being without capable adult supervision.

Second, on 12 April (having remained in Durham for two weeks), Cummings drove 25 miles from his parents’ house to Barnard Castle. The relevant criminal law for our purpose was, again, S.I. 2020/350. Did Cummings have a ‘reasonable excuse’ for leaving his parents’ house? Cummings’ explanation was that he drove to test his eyesight. Having recently been experiencing problems with his vision, Cummings said that he drove the short distance to Barnard Castle to test his capabilities before undertaking the far longer journey back to work in London.

The third instance also concerns the Barnard Castle incident. A road traffic law is now in issue. Road Traffic Act 1988, section 96, criminally proscribes driving a motor vehicle on a road with defective eyesight. There is no room to justify transgression of this standard. Driving with poor eyesight is a criminal offence.

Did Cummings break the law on any of these occasions? The first two instances, which can be taken together, do not admit of a clear answer. Cummings needed to have ‘reasonable excuse’ to leave his residence, but ‘reasonable excuse’ is nowhere defined in the Regulations. The thirteen examples of decidedly reasonable excuses provided at reg 6(2) (e.g. “to obtain basic necessities”, “to seek medical assistance” etc.) are non-exhaustive. That is, a court may find someone had a ‘reasonable excuse’ even if their behaviour falls outside the given list. However, it was suggested by Durham Police on 28 May that Cummings might have been without reasonable excuse when driving to Barnard Castle; that the trip “might have been a minor breach of the regulations that would have warranted police intervention”. Impunity, in these circumstances, may suggest non-conformity with the rule of law.

The third instance is yet more suggestive of a criminal offence. Sir Peter Fahy, former Chief Constable of Manchester Police, stated that the drive to Barnard Castle “certainly appears to be a breach of the Highway Code” and that “it’s not the way to test your eyesight… [to] put, potentially, other people in danger”. Similarly, John Apter, Chair of the Police Federation for England and Wales, advised that “[i]t’s not a wise move” to test your eyesight by driving. “If you’re feeling unwell and your eyesight may be impaired, do not drive your vehicle”.

Folks, I say this in all sincerity and as an important road safety issue. If you’re feeling unwell and your eyesight may be impaired do not drive your vehicle to test your ability to drive. It’s not a wise move.

— John Apter (@PFEW_Chair) May 25, 2020

These statements impliedly treat as established facts that Cummings’ vision was impaired, and that he drove a motor vehicle on the road. Those are the only ingredients for the section 96 offence, and they are here treated as being fulfilled.

It appears, then, that Cummings broke criminal laws in March and/or April earlier this year. The police’s failure to prosecute Cummings can be interpreted as non-conformity with this criterion of the rule of law.

Conclusion

The coronavirus pandemic has presented, and continues to present, immense legal challenges. This mini-series of articles has found that, in meeting these challenges, the government’s response has deviated from Joseph Raz’s formal understanding of the rule of law in several respects.

The coronavirus laws are unclear, long, vague, fast-changing and unhelpfully blur into legally ineffective government guidance. The government’s response to coronavirus failed to ameliorate (or, have contributed to) the inaccessibility of criminal courts. Principles of natural justice have been violated through the prosecution of Londoners behind closed-doors under the Single Justice Procedure. Finally, the police failed to prosecute a senior political adviser, notwithstanding that he may well have broken coronavirus-related and ordinary criminal laws.

Pointing toward compliance with the rule of law, however, it was observed that the coronavirus laws are prospective, suitably empowered by an enabling statute and are subject to review by the courts. Furthermore, the independence of the courts throughout the pandemic has remained unshaken.

Importantly, the findings against the government do not, by themselves, constitute material criticism. Even Raz recognised that the rule of law has “prima facie force” only — that it may be appropriate to deviate from strict adherence to the rule of law, if that is necessary to vindicate some other more important aim. One might argue, for example, that to create a legal response to coronavirus that effectively protects public health, it is quite necessary to ride as roughly over the rule of law as the government have been found to have done. I leave that final assessment to the reader.

Jordan Briggs graduated in law from the University of Oxford and began an LLM at the LSE in September. He is an aspiring barrister.

Please bear in mind that the authors of many Legal Cheek Journal pieces are at the beginning of their career. We'd be grateful if you could keep your comments constructive.