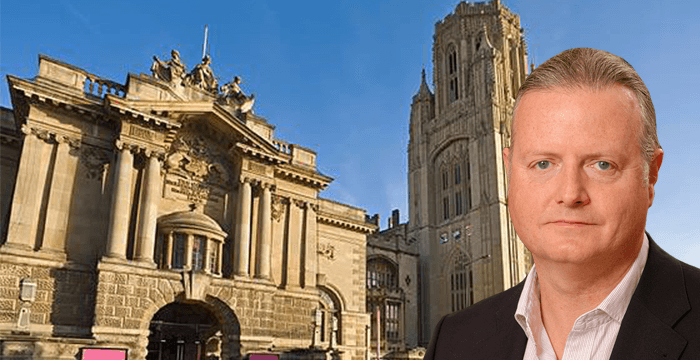

Ahead of the Future of Legal Education and Training Conference 2019 on Wednesday, Ken Oliphant, head of Bristol University Law School, explains why he foresees only tweaks around the edges to the traditional LLB

Change is coming. From September 2021, the new solicitor super-exam will replace the Legal Practice Course (LPC) and the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) — sounding the death knell for the existing route to qualification as a solicitor.

But not all universities will be embracing the overhaul. According to Ken Oliphant, head of the University of Bristol Law School, the main reservation lies in the exam’s content. SQE1 will cover key black letter law, including civil and criminal procedure, areas not usually explored on the ‘traditional’ undergraduate law degree. Similarly, SQE2 will test future lawyers’ practical skills such as advocacy and client interviewing, which are currently assessed on the LPC.

For some universities, the SQE’s practical outlook works to their advantage. “Those universities with a greater vocational focus that offer students a skills-focused path will likely see the SQE as an opportunity to provide a ‘one-stop-shop’ that gives undergraduates a law degree and preparation for the SQE,” Oliphant says.

Indeed, several universities have already come forward with plans to provide combined LLB-SQE courses, ensuring students will be ready to take SQE1 upon graduation. The ‘one-stop-shop’ will also allow aspiring lawyers to save money, too: rather than fork out extra cash on a SQE prep course, costs will be included in their undergrad fees, which can be covered by government student loans.

However, the same cannot be said for traditional Russell Group universities, including Bristol, which are more “conservative” in how they teach law, Oliphant explains. Their main concern being that the SQE’s practical focus extends beyond the remit of their existing law degrees rooted in academic research-led teaching. He tells us:

“For the University of Bristol, the SQE presents too much of a disruption for our teaching model. It would require us to hire new staff with a new skill set, which would be detrimental to the research focused and research-intensive educational programmes that we provide — and this is the same for more research-driven Russell Group universities.”

It’s for this reason that Oliphant does not foresee Bristol offering an SQE-facing law degree anytime soon. “We’ll continue to provide foundational knowledge in those areas, but Bristol, like other universities, is not going to offer any labelled SQE preparation units,” he explains.

That’s not to say that the super-exam will simply pass Bristol by. “It’s given us a bit of a nudge in re-thinking the skills graduates need for their legal career — beyond the traditional emphasis on reading, writing essays and prepping for exams,” says Oliphant, who will speaking at Legal Cheek’s Future of Legal Education and Training Conference 2019 on Wednesday. This fresh approach includes the law school’s plan to embed extra-curricular activities such as mooting and client interviewing into the assessed core curriculum of its LLB. Doing so, Oliphant believes, will take the pressure off law students who, despite facing huge academic workloads, “feel obliged to complete co-curricular activities in order to complete their CV”. Although Bristol does not aim to produce SQE1-ready students upon graduation, Oliphant believes it will put students in good stead to take the exam following a short SQE prep-course.

When applying for training contracts, Oliphant is confident that it will be a candidate’s undergrad law degree rather than their SQE score that will help them stand out: “Russell Group universities carry a quality mark for the reputation of their law schools within the legal sector, which will help students transition into legal practice,” he says.

In contrast, Oliphant questions whether law firms will rely on the SQE as a good indicator of candidate quality. He points to the super-exam’s heavy use of computer-based multiple-choice questions (MCQ) as an example. While the assessment has yet to be finalised by Kaplan, the education giant tasked with developing and delivering the SQE, universities and law firms alike have expressed concerns that the MCQ format will end up testing memory rather than legal knowledge. Oliphant explains:

“It’s regarded as a retroactive step in terms of legal education for future generations because instead of expanding the range of assessment measures, the SQE1 narrows it to a set of multiple-choice questions. If you narrow the assessment methods, you narrow the skills you’re testing.”

Professor Ken Oliphant will be speaking during the headline afternoon session, ‘The SQE: Next Steps’, at the Future of Legal Education and Training Conference 2019 on Wednesday 22 May at Kings Place London. Final release tickets are available to purchase.